Fishing can be considered a game of cat and mouse. You feel the rush when there is that tug on your line and cannot wait to see what is on the other end.

Now, imagine that feeling if you are a marine biologist on a shark tagging trip.

“The first ones are always one of the most special ones,” said Dr. Dan Abel, a marine biologist at Coastal Carolina University. “We never know what we are going to pull up when we set a long line. Or what we will see when we are on the way to set a long line.”

Abel, who has more than 30 years of experience researching sharks, has been shark tagging in Winyah Bay for more than 15 years. He started the program to give his undergraduate and graduate students a chance to study Juvenile Sandbar sharks.

Abel says shark tagging allows researchers the chance to study the movements of these ocean predators and why they like to frequent certain waters over others. The sharks can have a tag placed near the shark’s dorsal fin, or they can have an acoustic telemeter inserted into the abdomen of the shark.

Acoustic telemeters are little pingers that ping every 60 to 90 seconds. For researchers to get information on where the shark is, it has to go by an acoustic receiver.

Abel says Winyah Bay is so diverse and offers many surprises every time they head out to fish.

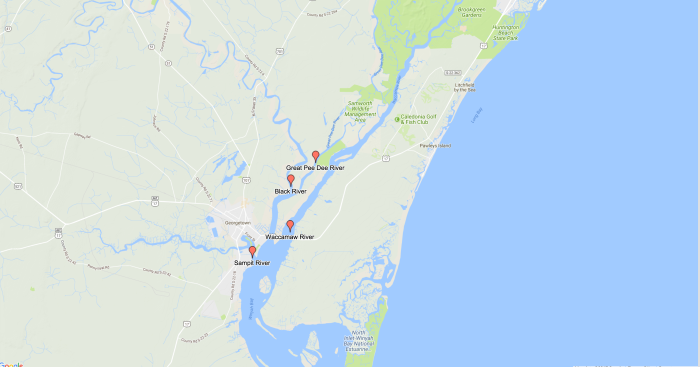

“What’s always surprising to me is the diversity and abundance of sharks and the size range in such a small ecosystem,” said Abel. “Winyah Bay has a very large watershed. It drains 18-thousand square miles, but the bay itself is not that large for it to have that many sharks and rays inhabiting it.”

Think of Winyah Bay as a hunting ground, where it comes down to the survival of the fittest.

“We have learned there is a mix of sharks within the bay, and they tend to divide themselves so the small ones can find safety and the big ones can find plenty of prey and room to swim around,” said Abel.

So, what is the draw for the sharks?

“We have learned that most of the sharks like high salinity waters, so it’s an estuary,” said Abel.

Salinity is the amount of dissolved salts that are present in water. It is that salinity that Abel says plays a role in why sharks visit Winyah Bay.

“The sharks will divide themselves based on salinities. Most of the big sharks, the oceanic or the near coastal sharks like high salinities,” said Abel. “Some of the smaller life stages we see will move up the river, and that will protect them from the bigger sharks.”

Salinity levels in Winyah Bay fluctuate because it has four rivers dumping into it.

“When there is a lot of rain in the water shed, the fresh water coming out can be quite significant which can lower the salinities, and not many sharks can live in low salinities,” said Abel.

To follow Abel and his students on their shark tagging trips to Winyah Bay click on the Coastal Carolina Shark Research team page on Facebook.